Too many floods

In 2017, floods in Penang displaced more than 7,000 people, impacted 159 areas, claimed 7 lives, and caused economic losses exceeding RM250 million.

From 2020 to 2023, flash floods have repeatedly disrupted daily life, leading to evacuations, traffic chaos, and significan damage to infrastructure.

— Picture by KE Ooi

There are areas in Penang at a higher risk of flooding. A common reason is that drainage systems are old—which increases the risk of floods.

Flood maps are contributing to Penang’s planning and mitigation efforts.

Too little clean water

Water demand growth in Penang was steady from 2010 to 2020, followed by a sharp increase between 2020 and 2022—that caught the water system unprepared. Demand decreased slightly in 2023, but water usage remains above pre-2020 levels.

Penang depends on surface water and external sources like sungai Muda to provide water to communities. Water levels have been declining due to climate change, which is increasing the pressure on the water supply.

Interruptions in water supply also disrupt Penang's electronics manufacturing and other high-tech industries, affecting jobs and causing economic losses.

Little nature to absorb

Areas that are easier to access tend to attract more businesses and services—driving economic growth. In 2020, buildings were more concentrated on Penang Island than in Seberang Perai, especially near the Penang Bridge and the airport. But with more concrete and less green space, these areas face higher risks of flooding and extreme heat.

It's becoming too hot

In February 2024, MetMalaysia issued a Level 1 heatwave warning as temperatures in Central Seberang Perai stayed between 35°C and 37°C for three consecutive days.

Rising temperatures and high humidity made it difficult for some people to cool down, increasing cases of heatstroke, dehydration, and heat exhaustion.

Penang’s entrepreneurs are also affected, as tourists are avoiding the months of extreme heat, reducing revenues for hotels, restaurants, and local businesses. This is leading to increased job insecurity.

Nature needs to come back

Introducing nature to cities helps reduce surface temperatures and improve urban liveability.

Planting trees along streets, creating rooftop gardens, and establishing blue-green corridors are some of the actions that cities are implementing to mitigate the Urban Heat Island effect.

The thermal images from George Town show that streets with shaded tree cover are significantly cooler. Temperatures in these areas were around 28.6°C, compared to 33.0°C in exposed areas.

Economic dependency

Penang is among the top five states in terms of its contribution to the economy of Malaysia, but GDP per capita is only half of Kuala Lumpur’s.

2021 had the highest growth rate among Malaysian states, surpassing the pre-pandemic level.

This growth was mainly driven by a robust recovery in the manufacturing and construction sectors.

There are more job opportunities in the south of Seberang Perai than in the northern region—as industrial areas like Batu Kawan and Simpang Ampat offer work in factories and transport.

A similar trend can be observed on Penang Island. On Penang Island, the economy is more focused on services like tourism, retail, and office jobs.

Penang is the largest contributor of the Malaysia’s

electrical and electronics products.

The dependence to a small number of industries limits Penang's capacity to adapt and thrive in evolving economic landscapes.

The comparison of Penang’s urbanisation over 1994, 2009, and 2024 reveals differences in its landscape and infrastructure

People need homes

Either people do not find a house or they can not pay it. For many lower- and middle-income households, homes are simply too expensive.

A home is usually considered affordable if it costs around three times the average annual household income. In 2014, Penang’s ratio was 5.2 times—making housing highly unaffordable.

Home ownership has also dropped, from 82% in 2014 to 78.9% in 2019—as incomes haven’t kept up with rising property prices.

Income is not enough

In Seberang Perai, 80% of official districts have median household incomes below the state average. This means a large part of the population struggle to afford good housing. Income gaps also limit access to homes with proper drainage and transport links—making them more exposed to natural disasters and health crises.

The housing shortage also makes it hard to keep and attract workers, which hurts Penang’s ability to attract skilled professionals to grow its economy.

Too many cars

More people mean more traffic congestion, longer travel times, and more fuel use.

This harms air quality, public health, and how livable the city is. Businesses face delays in moving goods and workers, which hurts the economy.

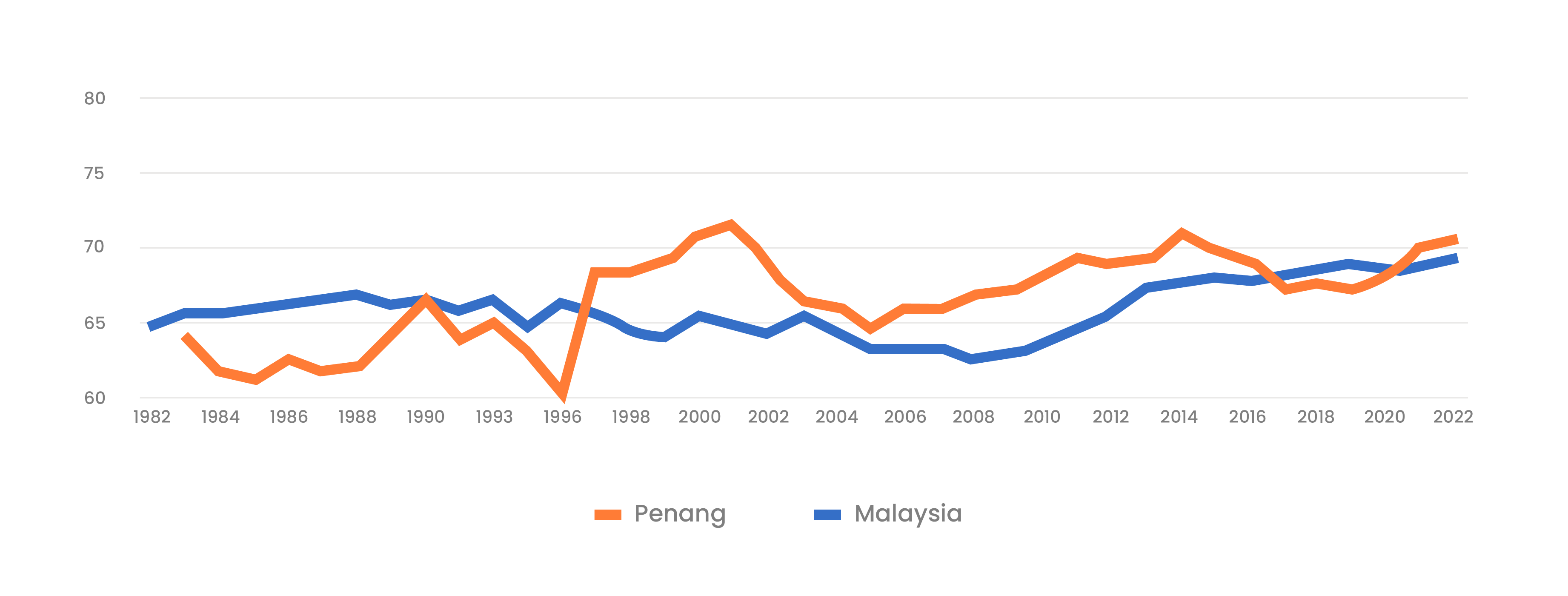

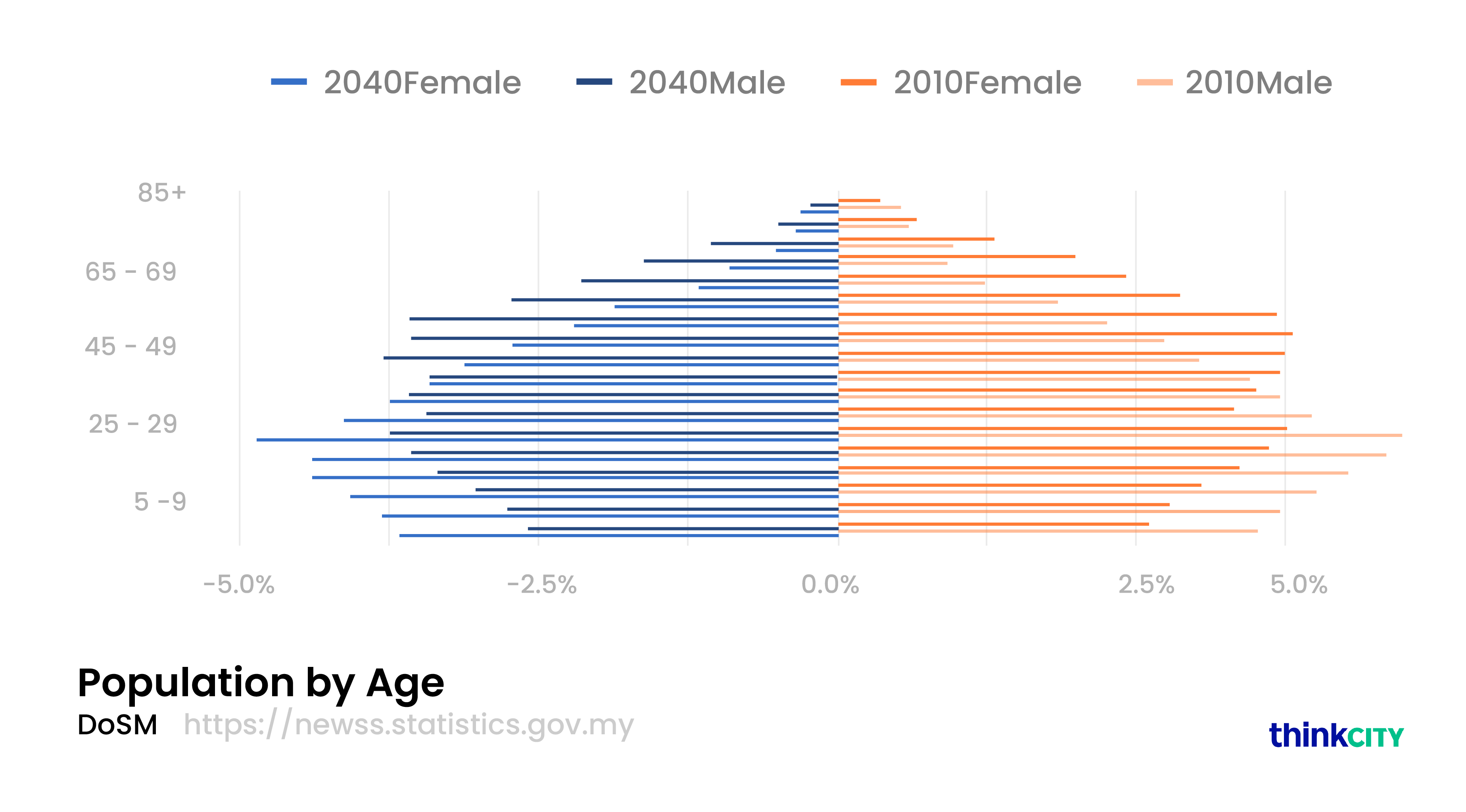

People are leaving

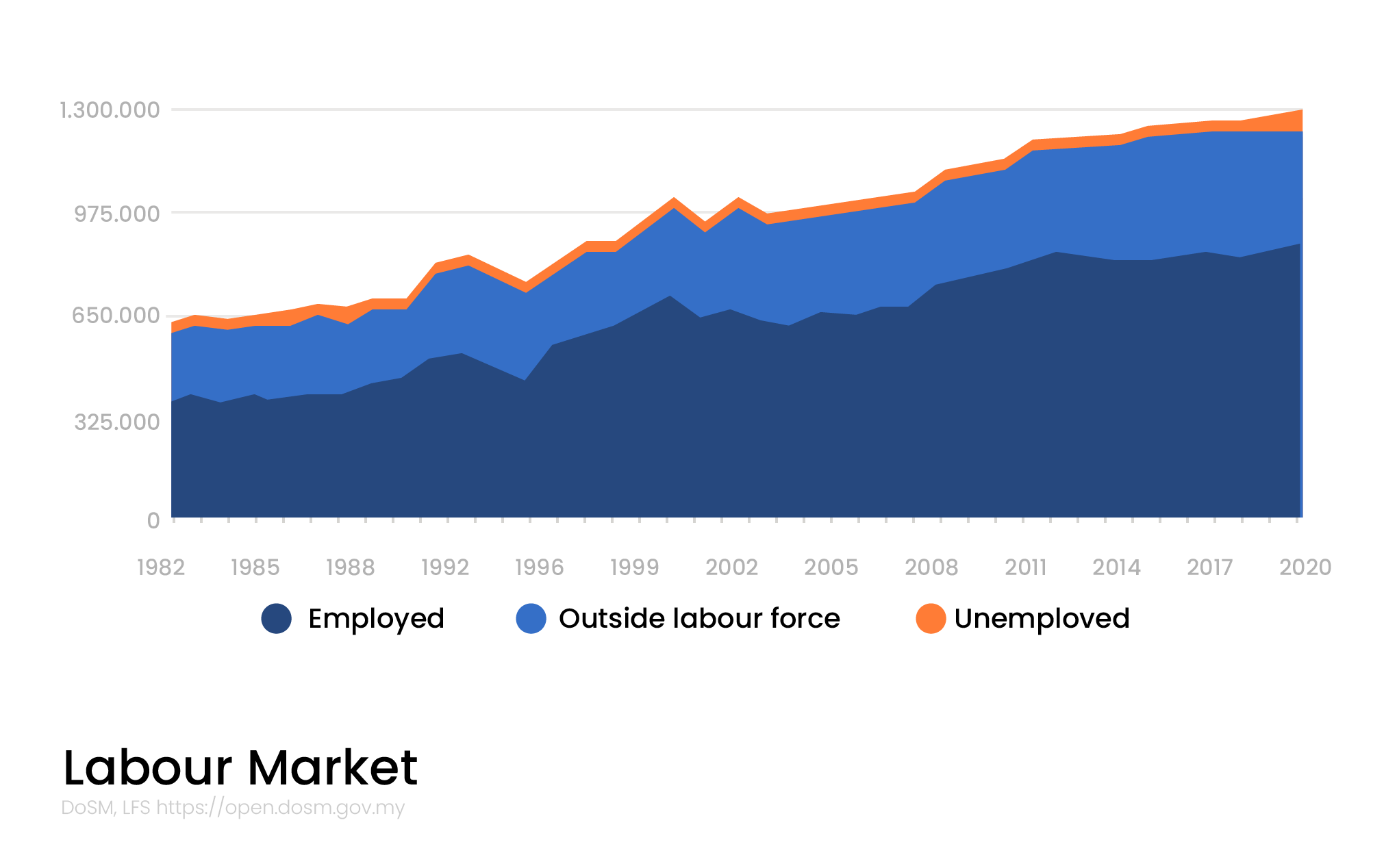

Ageing population and talent migration can lead to reliance on outside labour force —as local available labour reduces.

A resilient economy requires talent retention and attractive opportunities.

in Penang

The starting point of a successful resilience strategy is having resilient institutions and networks within the state and cities. Their capacity to collaborate and advance resilient solutions determines the state and cities’ speed of preparedness. So, does Penang have what it takes?